How red states are redefining taxpayer-funded education

The Florida House on Friday overwhelmingly approved a bill that would expand the state’s education savings account program.

Republican-led legislatures are fast-tracking bills that would redefine publicly funded education by giving parents state money to spend on private school tuition and homeschooling supplies.

Arkansas, Iowa and Utah this year have expanded or created “education savings accounts” open to all children who don’t attend public school. The Florida House on Friday overwhelmingly approved a bill that would expand the state’s education savings account program, as lawmakers in Kansas, Ohio, Texas and several other red states also consider universal accounts.

The flood of legislation comes as Republican leaders push to give parents control over their childrens’ educations and to restrict how public schools teach young people about racism, sexual orientation and gender identity.

“This year is basically the year of universal school choice,” said Robert Enlow, president and CEO of EdChoice, an Indiana-based group that advocates for school choice programs. “So many states are saying, we just think dollars should follow kids.”

Unlike traditional school vouchers, the state-funded accounts can be used to pay for a variety of education expenses.

Democrats and public school teachers oppose the proposals, saying universal education savings accounts are a handout to wealthy families that could erode funding for cash-strapped public schools.

Democrats and some fiscal conservatives also balk at the cost of universal programs and have argued that the programs don’t do enough to make sure taxpayer dollars are well-spent. Some Idaho Senate Republicans joined Democrats to vote down an education savings account bill last month.

“We all have the responsibility to make sure our budget is balanced,” Sen. Scott Grow (R) said on the Senate floor. “I can’t even decide how to balance the budget if I don’t even know what this is going to cost.”

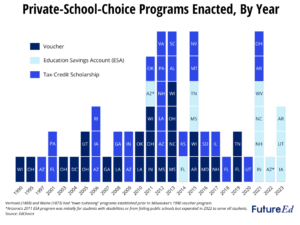

The first U.S. school voucher programs were created in the 1990s to help low-income children or children with disabilities afford a better education at a private school, researchers who study school choice policies say. Some state programs ran into legal trouble, however, because many state constitutions ban lawmakers from spending taxpayer dollars on religious schools.

So state lawmakers turned to tax-credit scholarships, which give people and businesses a tax credit for donating to nonprofits that fund school vouchers.

Education savings accounts are the latest innovation. They avoid constitutional problems and let parents spend taxpayer dollars on private school tuition, religious school tuition and a range of educational expenses, such as tutoring, transportation and standardized test fees.

School choice researchers say both qualities appeal to Republicans.

Universal accounts are “sort of the ultimate form of parental empowerment,” said Chester E Finn Jr., senior fellow and president emeritus of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative-leaning think tank and foundation that advocates for high academic standards and charter schools.

“It goes beyond picking a school, and it goes beyond influencing what is in that school,” he said. “It actually goes to — here’s the wherewithal to spend on whatever form of education you think your child should have.”

Five states have created universal education savings account programs, including the three so far this year, according to EdChoice. Six others have established programs for students with disabilities and students from middle- and low-income families.

Education savings accounts typically give parents access to all or most of the money the state would otherwise spend to educate their child in a public school. Some states limit the number of students who can participate in their programs, but others do not.

The programs place some limits on how parents can use the money and include some accountability provisions, such as audit requirements. Arkansas’s new law doesn’t let parents use the money to buy TVs or video game consoles, for instance, or to pay tuition at non-accredited schools.

Democrats say the programs divert money to more affluent families at the expense of public schools.

“Taxpayers should not subsidize the rich to pay for private schools,” Florida Rep. Patricia Williams (D) said during an online press briefing last week. “That’s a big problem for me.”

Florida Democrats are pointing to Arizona’s experience as an indication of who benefits from universal education savings accounts and how the costs of such programs can balloon.

Arizona’s GOP-led legislature in 2022 expanded the state’s education savings account program — previously limited to students with disabilities, students with parents in the military and some others — to all students not in public school.

State fiscal analysts initially estimated the expansion would cost $33.4 million this fiscal year and $64.5 million next year. But enrollment soared from about 12,000 last summer to over 44,000 today, pushing unbudgeted costs past $200 million this year alone.

Most participating families were likely already paying for private school or homeschooling their children. Three-quarters of the first 6,494 applicants for the universal accounts had never attended public school in Arizona, the state’s education department tweeted in August.

Some Arizona account holders also are spending the money on questionable expenses, such as trampolines and tickets to SeaWorld, nonprofit news outlet The 74 reported last month.

Gov. Katie Hobbs (D) wants to scale back the program, saying in her January State of the State address that “the previous legislature passed a massive expansion of school vouchers that lacks accountability and will likely bankrupt this state.”

Florida Republicans dismiss those concerns. Rep. Kaylee Tuck (R), sponsor of the bill that would expand education savings accounts and other Florida school choice programs, has stood by legislative analysts’ estimate that universal accounts would cost Florida an additional $209.6 million next fiscal year.

She said on the House floor Thursday that Florida’s program would impose more requirements on participating private schools than Arizona’s does, and that Florida’s initial fiscal estimate assumes a larger jump in enrollment than Arizona’s did.

Democrats who oppose the Florida school choice expansion argue that while the state strictly regulates public schools, such as by requiring teachers to have certifications, those rules don’t apply to private schools.

“Are these [private] schools allowed to teach that the earth is flat?” asked Rep. Anna Eskamani (D) during Thursday floor debate. “Do they have to teach evolution?”

Republican lawmakers say parents will decide which programs and approaches are best for their families.

“Private schools are far more accountable than government-run schools because they are accountable to parents,” Rep. Randy Fine (R) said during a subcommittee hearing Friday. “And I do not believe that parents are going to allow their children to go year, after year, after year to a bad school.”

Finn of the Fordham Institute said decades of studying school choice policies have taught him that governments have to set some rules and standards to make sure students are getting a good education.

“Parents don’t always make good choices,” he said. Sometimes parents are hoodwinked by school operators, he said, or settle for nearby schools, or have personal struggles, such as battles with substance use, that prevent them from monitoring their children’s education.

Patrick Wolf, a professor of education policy at the University of Arkansas College of Education and Health Professions, said researchers have yet to evaluate how any education savings account program serves children. That’s because most programs don’t require students to take tests that researchers can study.

“There’s not a lot of data, there’s not a lot of reporting, there’s not a lot of transparency,” said Kevin Welner, professor at the University of Colorado Boulder’s School of Education and director of the National Education Policy Center, a research group at the university.

Education savings account backers say the programs have enough safeguards, Finn said. “They might be right,” he said. “But the jury is still out.”