At least 45% of tap water in the United States could have at least one PFAS chemical, a first-of-its-kind nationwide testing model found.

A study released Wednesday by the U.S. Geological Survey is the first broad-based test of private and government-regulated public water supplies. The figure of contaminated water represents an estimate of the nationwide impact of the “forever chemicals” known as per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances.

The USGS, part of the U.S. Department of the Interior, tested for 32 types of the more than 12,000 PFAS chemicals, not all of which can be identified in testing.

“USGS scientists tested water collected directly from people’s kitchen sinks across the nation, providing the most comprehensive study to date on PFAS in tap water from both private wells and public supplies,” said USGS research hydrologist Kelly Smalling, the study’s lead author.

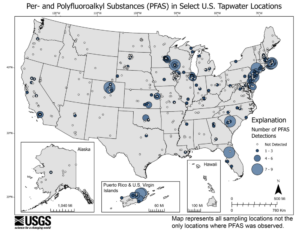

Samples were taken from 716 locations that included a range of human-impacted areas. Most of the water found to have a PFAS chemical was observed near urban areas and potential PFAS sources, the study found.

The study comes after at least 18 states sued the makers of PFAS chemicals, seeking damages for polluting the environment, including drinking-water sources, and the investigation and removal of PFAS contamination from natural resources.

The companies are facing thousands of lawsuits and have already paid out major settlements. 3M agreed to a $10.3 billion settlement last month to cities and towns to test for and clean PFAS-contaminated drinking water. Also last month, chemical companies DuPont, Chemours and Corteva announced a $1.18 billion class action lawsuit settlement.

States are also seeking to limit the use of PFAS through legislation. Minnesota enacted a law in May that requires PFAS labeling and bans certain items containing PFAS, including carpets or rugs, cleaning products, cookware, cosmetics and dental floss.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced last week its new framework for ensuring that new PFAS and new uses of it will not contaminate people or the environment. The agency stated that quantifying the risk of the chemicals has proved challenging in the past.

“For decades, PFAS have been released into the environment without the necessary measures in place to protect people’s health — but with this framework, EPA is working to reduce the risk posed by these persistent contaminants,” said Michal Freedhoff, EPA assistant administrator for the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention.

Humberto Sanchez contributed to this report.