Death of Conn. lawmaker spotlights wrong-way driving deterrence efforts

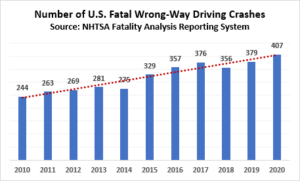

States are trying various countermeasures as fatal wrong-way crashes increased by two-thirds from 2010 to 2020.

An alarming rise in wrong-way driving fatalities has led several states to install new warning systems designed to alert the errant driver and, in some cases, the police and other motorists.

The issue took on particular significance in Connecticut where earlier this month state Rep. Quentin Williams (D), 39, was killed by a wrong-way driver, who also died, while returning home from Gov. Ned Lamont’s (D) inaugural ball.

“We have a profound sense of purpose around this,” said state Sen. Christine Cohen (D), the Senate chair of the Connecticut General Assembly’s transportation committee.

There was already growing concern in Connecticut about wrong-way crashes before Williams’s death. In 2022, 23 people died in 13 collisions involving a driver who was traveling on the wrong side of the road, a dramatic increase over previous years.

Nationally, fatal wrong-way crashes increased 67% from 2010 to 2020, according to Richard Retting, a senior program officer with the Transportation Research Board, a division of the National Academy of Sciences. By comparison, overall crash fatalities increased 33% during the same period.

“Human behavior is at the root of many wrong-way driving crashes, particularly alcohol impairment,” Retting said.

Courtesy of the National Academy of Sciences

Connecticut is among more than half-a-dozen states that have installed deterrence technology in an effort to address the rise in wrong-way crashes. The list includes Arizona, California, Florida, Massachusetts, Nevada, Oklahoma, Rhode Island and Texas.

From 2004 to 2011, Texas, California and Florida recorded the highest rates of fatal wrong-way crashes.

While still relatively rare, these crashes are more likely to result in serious injury or death because they often occur at high speeds and involve two vehicles colliding head on.

The countermeasures that states are deploying include more prominent do-not-enter signs and flashing lights that are triggered when a car begins to enter a highway via an exit ramp.

In some states, the detection technology can alert the state police and even send a message to highway reader boards to warn drivers who are in the path of the wrong-way car.

Retrofitting an exit ramp can cost a few hundred dollars for new signage and up to $50,000 or more for a full-blown detection system.

Despite the technological advances, efforts to combat wrong-way driving are still in the “learning and trialing” stage, according to Aaron Lockwood, director of business development for Carmanah, a British Columbia-based traffic safety company that contracts with U.S. states.

“Wrong-way driving has been in the tire kicking phase for over a decade,” Lockwood said. “It’s always been known to be a problem, but the trick is how can you come up with something that is high bang for the buck.”

Lockwood said the primary goal of any wrong-way driving countermeasure is to get drivers to self-correct.

In 2018, the Arizona Department of Transportation began piloting the use of illuminated warning signs and thermal detection cameras in the Phoenix-metro area to identify wrong-way drivers getting on the freeway. Described as a first-in-the-nation approach, when triggered the cameras send an immediate alert to the DOT and Department of Public Safety so that troopers can be dispatched and highway alert signs activated.

The pilot project found that 85% of drivers turned around before entering the freeway.

ADOT has since expanded the technology to other locations in the Phoenix area and has plans to deploy the cameras in other parts of the state contingent on funding and access to fiber-optic infrastructure.

“Technology can’t prevent all crashes from happening, but it can speed law enforcement’s response times and allow our agency to quickly post warning messages for other freeway drivers to see,” said Doug Nintzel, an ADOT spokesperson, in an email.

Florida, Rhode Island and Texas are among the states that use dynamic message signs to warn oncoming motorists of a wrong-way driver headed their way.

In 2016, the Nevada Department of Transportation received approval from the Federal Highway Administration to experiment with “red rectangular rapid flashing beacons” at certain interstate ramps. Between June 2020 and June 2022, the system identified 189 wrong-way drivers, 78% of whom stopped before entering the freeway, according to NDOT.

This year, NDOT plans to spend $2 million to install the technology at additional ramps between Reno and Carson City and in the Las Vegas area.

“At these locations, we will also incorporate newer technologies using radar and multiple sets of closed-circuit cameras … to help improve the level of success in detecting and reversing wrong-way drivers,” Meg Ragonese an NDOT spokesperson, said via email.

In 2015, the Connecticut Department of Transportation began installing oversized warning signs at 700 off-ramps. The state also placed “Wrong Way” signs on the back of speed limit signs as a repeated alert to drivers headed the wrong way.

Last year, Connecticut lawmakers appropriated $20 million for the Department of Transportation to retrofit dozens of exit ramps with new flashing lights and other countermeasures.

CTDOT and its contractor plan to upgrade 70 locations over the next year. A total of 236 highway exit ramps have been identified as high risk.

“We’re just working our way down that list,” CTDOT spokesperson Josh Morgan said.

CTDOT is also developing new pavement and guardrail markings that appear white to a driver going the correct direction but display as red to a wrong-way driver.

“Red flashing lights, red wrong way signs, red reflectors in the pavement, red reflectors on the guide rails — trying to get as many visual cues to the driver that they’re heading in the wrong direction,” Morgan said.

Connecticut’s system does not automatically alert the state police. But a pilot project on I-91 in the Hartford area will include that capability.

Later this year, the National Academy of Sciences plans to release a sweeping report on wrong-way crashes. The report is designed to serve as a guidebook for state transportation departments with the goal of encouraging “more systematic and uniform installation” of wrong-way driving counter measures.

“The emphasis of this study was to understand … what tools are currently available and have evidence to support them,” Retting said.

Cohen, the Connecticut transportation chair, said she expects her committee to do a “deeper dive” on the issue of wrong-way driving during the 2023 session as part of a larger effort to address an overall rise in traffic fatalities.

“I absolutely do think we should be doing more,” Cohen said.